Interview with

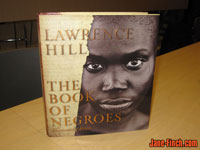

Canadian author Lawrence Hill (The Book of Negroes)

January 19, 2010

Mr. Hill read from his work as part of York University's Department of Humanities Canadian Writers In Person series. The series which is free and open to the general public, is also part of an introductory course on Canadian literature. For more information about the Canadian Writers In Person series, please click the links below: http://www.yorku.ca/laps/canwrite http://cwip.artmob.ca Transcription of the Q and A:  Jason

Roberts: Hi, this is Jason Roberts reporting for Jane-Finch.comÖ

Thanks for downloading the podcast. Jason

Roberts: Hi, this is Jason Roberts reporting for Jane-Finch.comÖ

Thanks for downloading the podcast.

On the evening of Jan. 19, 2010, York University welcomed Lawrence Hill, author of the celebrated novel The Book of Negroes; as part of its Canadian Writers seriesÖ In this podcast, we talk with Mr. Hill, as well as hear from people who were at the event, to hear their thoughts.... JR: Ö thanks very much for taking the time out to talk with us, Lawrence. My first question is: for the few of us who don't know what your book -- The Book of Negroes -- is about, can you just tell us a bit about what happens in the novel? Lawrence Hill: The novel, The Book of Negroes, traces the life of an 18th century African woman who travels around the world in and out of slavery from her homeland from a village in Mali in landlocked West Africa, to South Carolina, to New York City, where she serves the British in the American Revolutionary War, to Nova Scotia, and then ultimately joining an exodus of black Loyalists to Sierra Leone. And then finally to serve in the abolitionist cause in Britain. So it's really a novel that follows the life-long journeys of an African woman in the 18th century, in and out of slavery. JR: Okay so, what's the age range? Like in terms of the span? So at the beginning of the novel, she's how old? And by the end how old is she?

JR: Okay, it might seem like an obvious question, but why'd you write it? Why'd you write the novel? LH: I wrote it as an act of love. Really as a tribute to all of the people who have gone before us who have shown such strength, vitality and courage in the face of momentous difficulties. What amazes me isn't just that our ancestors survived the things they did physically, but that some of them obviously survived emotionally, too. And so I wrote it sort of as a hats off to the strength of the people who have gone before us.

LH: I think that we need to do more to recognize who we are. What our history is. What our culture is. Where we've come from and where we are now, and where we're going. Slavery is part of that, so we should know more about that, but we should know more about a lot of things. And as many are quick to point out, and it's worth saying, obviously our history isn't just history of slavery it's a history of survival; it's history of triumph. But we need to know more about a lot of things. It's worth stating, also, that slavery continues to exist to this day. Up to twenty to thirty million people around the world are currently enslaved, even though we are beyond the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. So, itís an ongoing social evil. JR: Youíve written many different genres. And I wanted to know what did you like most about writing historical fiction?What was the process like? In comparison to, say, writing just plain-old non-fiction?

JR: What sorts of things do you read? LH: Oh gosh, I read everything. Sometimes if I have Ė JR: What are you reading right now? LH: Um, right now Iím reading a new book by Andrea Levy, the author of Small Island. Sheís a Jamaican author, or at least an author of Jamaican decent who lives in London. And she wrote this great book called Small Island about Jamaicans in London during and after the Second World War. But, um, now sheís got a new book out about slavery, and Iíve just picked it up. So, Iím reading Ė well actually, itís not out yet, Iím reading it in draft form Ė so Iím reading Andrea Levyís new novel just before being published. JR: Out of curiosity, have you read Sacred Hunger? LH: By Barry Unsworth? He won the Pulitzer Prize, right? And, I know it has to do with the Middle Passage, as well. I have not. I looked at it when I was writing TBON and I thought, ďUmm, I donít want to read this right nowĒ, because it was too close to what I was working on. So I put it aside, and I didnít come back to it. So, I have not read Sacred Hunger but I know what itís about, and I know it earned him [Unsworth] a massive prize, and itís considered well regarded. But I havenít read it.

LH: Sure, yeah. Clement Virgo and Damon DíOliviera are the principals of Conquering Lion Pictures and itís a Canadian Film Company and theyíve optioned the book for film development and so weíve pretty well finished writing a treatment. And now, the process is to move into writing a screenplay, which I may involve myself in Ė we havenít decided for sure yet. So, basically they have the massive task of getting a script out, circulating it, and getting the financing, and making a movie, a big deal and a lot of work and they need to raise a lot of money. So, hopefully, itíll go well and get made, but right now itís in the very early stages of looking for financing and trying to get a script finished. JR: As a film, do you seeÖ do you see the bookÖ is there anything that youíd like to explore in the film that you maybe just lightly touched on in the book? Or anything that probably we might not be expecting -- do you see that happening with the film adaptation? LH: I think itís evitable that a film adaptation has to take a lot of liberties with the book. And youíre talking about a two, or two-and-a-half hour film that condenses a five hundred-page book Ė and, well you can really condense you just have to choose what to work on, and to dramatize that. I think the trick in a film is what to use, and what to dramatize, and what to just leave to the side and just say ďI --we canít do thisĒ, and so, the challenge will be what to focus on Ė how to dramatize it and how to the core of the story, in film. But itís so early in the process that I donít really have any clear answers yet about where weíre going to go because weíve just begun the process -- and itís a multi-year process. JR: Okay, so itís coming up to Black History Month, and I just wanted to know who you personally think is the greatest black Canadian?

JR: Okay, then I guess who would you see as a standout black Canadian trailblazer? LH: Well, there are many. So many. I guess Iíll just start with my own family because Ė and thatís not to say that the person Iím mentioning is more important than anybody else Ė but Iíll just start from a personal standpoint and the would be my father, Daniel Hill, who came to Canada as an African-American student right after the Second World War serving in the American army and started to study at the University of Toronto, having decided heíd never live in the United States again, never live in a segregated America again. Moved his life to Canada and raised his family here and became a passionate Canadian, devoted his life to human rights and to black history, and to the celebration of black history. So heís my father, and heís the one who first ignited my passions about history and about black culture and about black people and about black culture so I mentioned him first because heís the first one I met and heís in my own family, so Iíd start with him. He passed away a few years ago, and I still feel he speaks to me, and I still miss him. JR: Tonight there was talk about starting a letter-writing campaign to get your book included in the high school curriculum. How do you feel about that? LH: Well, Iíd love to see the book used more widely in the high school curriculum. Some schools are using it here and there. Iíd love to see it used in a more organized and complete way. But there are lots of books that should be studied and used and paid attention to and a lot of books that have been looked at too much that maybe should be put aside a little bit and made room for some others. So, yes Iíd love to see TBON used more in the schools.

JR: Seeing as weíre talking about the school system, Iím sure youíve heard about the black-focused school in Toronto, that actually located here in Jane and Finch. And I just wondered as you were talking, if you had any thoughts about a black-focused school, or the idea of a black-focused school? LH: My thoughts about the black-focused school here in Jane-Finch are that itís a worthwhile, and important, and worthy initiative. Our school system has failed black kids so miserably on the whole that I think that any innovative approach and every innovative approach should be considered and explored to try and improve our batting average and do a better job educating and exciting black kids about their futures, and about learning. I donít feel the black-focused school is the be all and end all solution to all the problem our educational system. But, that's okay; no one is pretending that it is. Itís one approach of many that can be attempted to try and improve the way that weíre teaching black kids and reaching out to them and including them in Canada today. So, if itís seen as one in a large tool, a large kit of implements to use to sort of excite and stimulate black kids in the school system, fine. But, obviously, it will only touch a tiny minority of all the black students passing through the school system, say, even in the GTA. And so even it were tremendously successful, itís one school influencing a very small number of students. So, if you look at it as an opportunity to learn and grow and teach and perhaps find some new ways of reaching kids, great, but itís not a solution unto itself. Itís one of many things that can be explored. JR: Just two more questionsÖ For those of us who have started writing, I wondered if you perhaps had any words of inspiration or any thoughts about how, how powerful writing can be? LH: Well, writing changed my life. And I think it changes profoundly the life of anybody who takes it up and does a lot of it and hopefully itíll change the life of the people who come to read what youíve written as well. Art is something that you do because you just have to. I mean you become an artist, I think first and foremost, because the world doesnít seem right unless youíre doing it. So, you do it really to save yourself, to find yourself, to express yourself, Ďcause you have to. And then of course if you have to, well, hopefully thereíll be institutions and an infrastructure there to support you. But I think that first and foremost art, including writing, comes from a necessity to sort of set the world right by writing about it, and making sense of it yourself. So itís a very powerful impetuous really. Itís a way of righting the world and making things more satisfactory, making sense of things that seem incomprehensible. So itís a survival strategy, I think, for those of us who do it. JR: Now youíve got a huge body of work. Do you have Web site? LH: Yes, I have a Web site. Itís www.lawrencehill.com. Yeah, itís been a good tool. Lots of people have come to it. And these days, most authors have Web sites, so people can find out more about them and so forth. I donít have Facebook or Twitter or anything but I do have a Web site and keep itÖ fresh! JR: Well thank you so much for talking to us. LH: Great to talk to you, good luck to all of you, and all who are listening... *** Dalton Higgins (author of Hip Hop World): The Book of Negroes, I mean you have, he [Lawrence Hill] explained it Ė he captured quite nicely in his lecture at the York University tonight, this whole idea of little-known histories of African peoples in the New World. And this idea of sort of a community of people repatriating itself back to the original homeland, you know? Something like a maroon culture, you know, and then saying, like, heading back to Africa, you know? Like itís a fascinating, brilliant, profound story, you know? And, um, if not for this book, I donít even think people would really be thinking about slave narratives and the repatriation of black communities, you know? So itís a brilliant piece of work... *** Dr. Gail Vanstone, Coordinator Culture & Expression Program, Department of Humanities, York University: You know, I mean everybody talks about how Canada, a lot of people donít know that Canada had slaves. And, um, so I think itís really important to know that story. Because as historians have said: if you donít know your history, youíre bound to repeat its mistakes. *** Have a story idea youíd like to see on Jane-Finch.com? E-mail webmaster@jane-finch.com |

||||